I was pleased to see Bishop Daniel Martins nod approvingly at my essay on our map of Anglican historical theology. He wrote on Facebook, “Some impressive analysis by Matthew Dallman, whose project it is to keep the work of Martin Thornton in front of Anglican eyes.” A blogger named JD Ballard responded, as well. Ballard comments:

I wonder if reacquainting ourselves with our fore-bearers in the faith might help us find our way forward… might lead us to a much longed for renewal.

My thoughts exactly. Renewal always involves returning to the sources — aka “back to basics”. And how to reacquaint ourselves, at the parish level, is precisely where my focus is right now. This is the “challenge” that I am choosing to face.

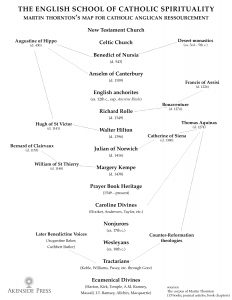

The works that make up our tradition do issue in a curriculum that is comprehensive and, in one sense, large. Just look at the map. But to be well-acquainted with it does not present itself, at least to me, as a thoroughly impossible task. There are many texts, but there aren’t that many. In even rougher outline — Augustine’s Enchiridion, Benedict’s Rule, Anselm’s Proslogion, Julian’s Revelations, and Macquarrie’s Principles of Christian Theology, all guided by the Book of Common Prayer — and that is plenty good food for a parish journey.

The works that make up our tradition do issue in a curriculum that is comprehensive and, in one sense, large. Just look at the map. But to be well-acquainted with it does not present itself, at least to me, as a thoroughly impossible task. There are many texts, but there aren’t that many. In even rougher outline — Augustine’s Enchiridion, Benedict’s Rule, Anselm’s Proslogion, Julian’s Revelations, and Macquarrie’s Principles of Christian Theology, all guided by the Book of Common Prayer — and that is plenty good food for a parish journey.

And of course, the concrete texts aren’t the whole story. Our theological tradition emerges from the marriage of texts within Anglican communities over our history. Our tradition, like any tradition, is what some call a “cultural-linguistic phenomenon”. That is fancy jargon. What is means is simple, however. How our conversation, as Catholic people in a variety of life situations and contexts, relates to the texts is as important as the actual words on the page. We are a family that lives around The Word. This life is through space and time. How we as Anglicans encounter The Word liturgically, sacramentally, corporately through the history of the Body of Christ makes for what we might call “our conversation” — all Anglicans, all Christians, all Saints, gathered around the table in conversation — listening to, feeding upon, and responding to, The Word. As Julian writes, “And what can make us rejoice in God more than to see in Him that He rejoices is us, the highest of all His works?” This is the essence of our conversation.

At St Paul’s Parish, our rector has charged us with a question: how do we communicate authentic Anglicanism to others?

My thought has been that before we talk it, we must know what “it” is. That is to say, we first must be able to identify our tradition. Hence the map, as a rough estimation of our tradition of theology as it has unfolded through history. That is step 1.

Step 2, therefore, after we know what “it” is, is clear: we must “live it”. We have to put ourselves in dialogue with these works, as best we are able, and make them our own (i.e., “appropriate” the texts).

As Ballard says, we ought “reaquaint” ourselves with our tradition. Start with Augustine, Benedict, Anselm, Julian, Macquarrie, and proceed as you will to the others. Perhaps this seems imposing. It has to me, to be honest. But I’m wondering now whether the task of doing so starts with an immediate recognition: we are already acquainted with this map — because of the Book of Common Prayer! We are “Prayer-Book Catholics”, and because we are, we are participating in the “Anglican conversation”, aka the map, by virtue of our liturgical life — what Thornton calls “the Catholic regula” of Mass + Office + Devotion. Our liturgy — which is to say, our form of Catholic liturgy — is both the source and summit of our experience. This is to say, our liturgy is the source and summit of our “Anglican conversation”, in its fullest, most supreme, most actualized sense. O Lord I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof. But only say The Word, and my soul shall be healed. Our liturgy feeds us. Furthermore, our liturgy is a school; it teaches our conversation.

To reacquaint is to listen. “Listen!” is the first word of The Rule of St Benedict. Thus the “how to reacquaint” method perhaps emerges: within our liturgical life in Anglican parishes (which in its fullest sense is both Mass and Office), we read devotionally in our parish study groups works from the map. We talk about them in our small groups, and we allow the Holy Spirit to feed us, lead us, and unite us. We simply intend, and follow through with, to listen to the Holy Spirit through the works of our tradition. Doing so does two things: (1) it renews our understanding of who we are as Anglicans — the nature of prayer in the Anglican tradition, and (2) it gives us vocabulary that builds upon the vocabulary supplied by parochial formation courses.

To reacquaint is to listen. “Listen!” is the first word of The Rule of St Benedict. Thus the “how to reacquaint” method perhaps emerges: within our liturgical life in Anglican parishes (which in its fullest sense is both Mass and Office), we read devotionally in our parish study groups works from the map. We talk about them in our small groups, and we allow the Holy Spirit to feed us, lead us, and unite us. We simply intend, and follow through with, to listen to the Holy Spirit through the works of our tradition. Doing so does two things: (1) it renews our understanding of who we are as Anglicans — the nature of prayer in the Anglican tradition, and (2) it gives us vocabulary that builds upon the vocabulary supplied by parochial formation courses.

These steps seem reasonable to me because we are already doing them. Yet to have the goal at least sketched out — the goal is to be able to respond to God in conversation with others — would seem to me to make the whole enterprise cleaner and more purposeful. Thornton, as usual, captures our task perfectly: “Any satisfactory spirituality … especially Anglican spirituality, can only evolve by serious study of our ancient tradition, plus bold experiment.” The task is ours to perform.